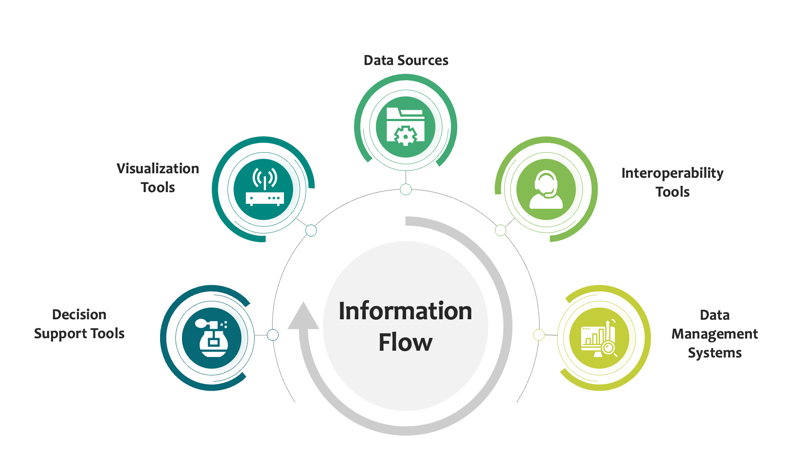

In the public health sector where majority of functions are done by siloed systems, interoperability is critical to systems implementation. Unfortunately, implementers either forget to include it in the system design and architecture or totally ignore the need. This issue has created multiple challenges ranging from constraining ministries of health to achieve their business objectives, to limiting the ability of using data from these systems to inform decision making. Occasionally, this issue has gone as as far as rendering the newly implemented systems obsolete, due to inability to perform their key functions because of absence of critical data from other systems.

At S4D, we consider interoperability a critical success factor when developing system architecture in our implementations. We ensure that each system we introduce in the Country’s eHealth architecture, at a minimum meets the integration requirements, could communicate with other systems in the IT ecosystem, and its data structure is aligned to the country’s data requirements and configurable to accommodate Global Standards, thus enabling exchange of information in multiple formats across the enterprise.

We view interoperability from three distinct perspectives, using the United States government, Healthcare Information and Management System Society (HIMSS) as our framework:

Foundational Interoperability

Where we consider that the systems, we implement have the capability to give data to another system, while also receiving data. Where we have implemented Logistics Management Information Systems (LMIS) we ensured that they can share and receive data from multiple Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) and other eHealth solutions both locally and globally within the ecosystem. For example, in Ghana, using the One Network architecture we managed to integrate the Ghana Integrated Logistics Management Information System (GhiLMIS) with District Health Information Systems (DHIS) enabling sharing of information between the supply chain and service solutions.

Structural Interoperability

Where we ensure that data transferred between systems is sent and received in formats that can be interpreted and understood by the two systems. We ensure that data is sent and received in a meaningful and shareable format and that information and meanings will not change even though the data may change hands. For example, in Ghana, we integrated the GhiLMIS with the Imperial Management Science (IMS) SAP software solution, using this approach. The integration ensured that irrespective of different solutions managing the Ghana public health supply chain transactions, the data that is exchanged stays meaningful and shareable to the end-users.

Semantic Interoperability

Where we have developed master data that supports the entire supply chain and structured it in formats that allow any system in the ecosystem to correctly receive and understand new data. The standardized coding has enabled us connect systems not only within in-country supply chain ecosystem but scaled up to include global solutions. With the master data that supports both our unique data structure and Global Standards like the GS1, we successfully integrated GhiLMIS with the GFPVAN. This is one of the unique occasions where an in-country supply chain solution has been successfully integrated with a Global Control Tower platform.

Our experience has shown that when interoperability is considered as a critical part of system implementation, project objectives are fully realized, and foundations are built for system agility within the IT ecosystem and ministries ability to sustain them. Interoperability will ensure that data is shared across the enterprise, improve service provision and patient care, while improving operational efficiencies and cutting down overall costs, enabling sustainable and resilient health systems.